Thought of the Week - The costs of a proper trade war with China

Putting tariffs on goods traded between China and the US/Europe has become fashionable across the political spectrum. Western political leaders, from Donald Trump to Emmanuel Macron, claim that China is undermining global competition with its enormous state subsidies. Meanwhile, China is protecting its domestic manufacturers from international competition through the use of retaliatory tariffs on Western goods. Where is this all going to end?

I sometimes feel like a dinosaur when I say I am a big fan of free trade and against all forms of trade barriers, especially tariffs. There is plenty of evidence that tariffs don’t work and, in the end, increase inflation without creating jobs or preventing job losses. Plus, in many cases, tariffs can be circumvented through third country trade, which is probably the best possible outcome once tariffs have been imposed because it keeps the negative impact on inflation and jobs to a minimum.

Be that as it may, the current US government has increased tariffs on Chinese goods dramatically and Donald Trump has indicated he is willing to impose tariffs of up to 60% on Chinese goods should he get back into power.

A 60% tariff would be unprecedented and we have no idea what kind of retaliation we would see on China’s side, let alone how global trade flows would rearrange themselves between the US and its European and Asian allies.

But what we can know is what happened in the past and this is where a study by the Bank of Spain comes in handy. The authors of the study looked at trade during the Cold War and reverse-engineered the tariffs that would lead to a separation of trade blocs similar to this episode.

Once the Cold War started, trade between the Eastern and Western blocs was severely restricted, essentially limited only to commodities and some basic industrial goods. As we know, this eventually hurt the Soviet bloc more than the Western bloc and led to the fall of communism in the late 1980s. But in the four decades of the Cold War, trade was separated into two distinctive blocs reflecting a geopolitical fragmentation not unlike the one that may be in our future should the trade war with China escalate.

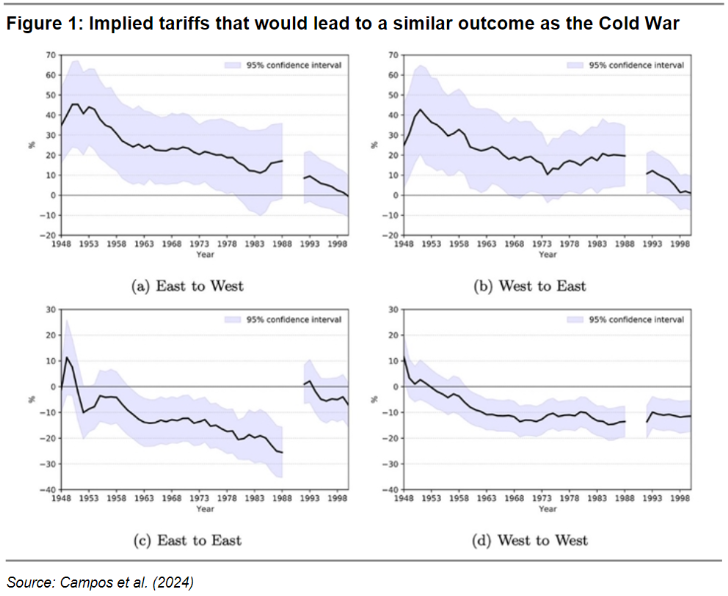

So, here are the implied tariffs that the study found would lead to a similar outcome as the Cold War. As you can see, the trade restrictions during that period imply a tariff between the East and West of more than 40% in the early 1950s and about 20% for most of the next four decades.

A 60% tariff on Chinese imports to the US would thus be roughly three times as tough as the Cold War restrictions. Back in the 1950s, countries within each trade bloc reacted to these large trade barriers by introducing free trade zones among themselves. The most prominent one of these was the EU, which effectively reduced tariffs for trade between European countries by more than 20%. But similar free-trade agreements also existed in the Eastern Bloc.

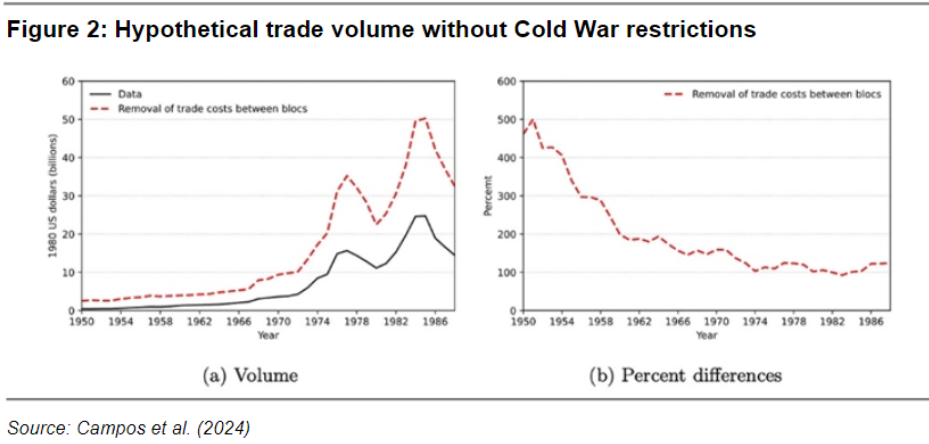

Yet, these regional free trade agreements were not able to overcome the burden put on consumers in both the East and West by the Iron Curtain. In a simulation, the authors of the study estimate that trade between the two trade blocs would have been up to five times higher in the 1950s without the trade restrictions, and even in the 1980s, trade would have been twice as high without the trade restrictions.

For us in the West, that reduced welfare and wealth by about 0.3% to 0.5% per year. And over 40 years, that meant that our living standards ended up some 12% to 22% lower than without the Cold War. Now, multiply this by three and you get a rough estimate of the long-term costs of an escalating trade war between the US and China, which some politicians (not just Trump in the US, but others in Europe as well) support.