Thought of the Week - Hitchhiker’s Guide to Investment Research, Part 2: Theory vs. Practice

Yesterday, I started my “Hitchhiker’s Guide” trilogy on investment research by pointing out that a good researcher should focus on what matters. I stressed that this means a focus on what matters in real life, rather than what should matter in theory. But, and this affects economists in particular and only to a lesser degree strategists and research analysts, too many people think that if they have a theory of how the world works, this theory justifies a certain approach to examining financial markets or the economy.

Benjamin Brewster wrote in the Yale Literary Magazine in 1882 something that has variously been attributed to Einstein, Yogi Berra, and others: “In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice, while in practice there is.”

Economics and finance are both social sciences, not natural sciences. That means there are immutable laws in economics and finance. Both the economy and financial markets are places where millions of humans interact with each other and human behaviour changes all the time depending on the circumstances. Yet finance theory says that a simple description of financial markets such as the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) should be sufficient to determine the return prospects of a stock. I’ll have more to say about the CAPM in the third episode of this trilogy, so let’s stick with economists, the prime suspects in applying dubious and incomplete theories to real-life markets.

I have written so much about defunct theories of inflation such as the monetarist approach that the quantity of money is somehow linked to inflation that I cannot even add all the links to previous editions of “Thought of the Day”. But for starters, look here and here. Similarly, economists and central bankers focus on inflation expectations as if these expectations were somehow linked to future inflation. Well, the empirical evidence says: they aren’t.

Another pet peeve of mine is purchasing power parity (PPP). PPP states that currencies of countries with higher inflation should devalue over time versus currencies of countries with lower inflation. The problem with this theory is that it assumes that all goods and services are perfectly fungible and that I can get a haircut in Angola if I think my haircut in the UK is too expensive.

Clearly, this doesn’t happen in real life due to something economists call “frictions”. This is why economists love to debate what kind of inflation measure one should use to calculate PPP. Consumer price inflation is obviously not a good measure since it contains services like haircuts that are hard to arbitrage.

So, they tend to use producer price inflation instead, since that basket contains predominantly wholesale goods that are widely traded. But that means that PPP can remain violated for a long time in the prices consumers pay on a daily basis. So, some economists have decided to create a special basket of tradable goods and services to calculate PPP. The differences in PPP for different measures of inflation are typically not large. They are large today because of the significant differences between producer price inflation and consumer price inflation, but most of the time, they are very small.

Let’s say, one concludes that – based on PPP calculated from consumer price inflation – the US dollar is overvalued versus sterling by 10%, and – based on producer price inflation – it is overvalued by 12%. What does that mean for your investments? Of course, if the dollar is overvalued by 10% or 12%, one should buy sterling and sell dollars. But has any economist ever mentioned, how long it takes to revert valuation differences from differences in PPP? Yes, PPP works, but it typically takes five to ten years or longer for PPP to adjust. That would mean that – based on the PPP example above – sterling should outperform the dollar by some 1% per annum to 1.2% per annum.

In case you don’t know, I tend to ignore such forecasts because the weekly or monthly swings in currencies are much larger than that. The noise around exchange rates is some five to ten times larger than the “signal” economists have given me about exchange rates.

And then, economists waste weeks and months debating whether to use consumer prices or producer prices to get a better estimate. The difference between the two estimates is some 0.2% per annum in our example or a factor of 25 to 50 smaller than the noise in real-life exchange rates. It’s an interesting discussion to have, for sure, but remember that economists and strategists working in finance are paid to help people make money. And PPP is simply a distraction.

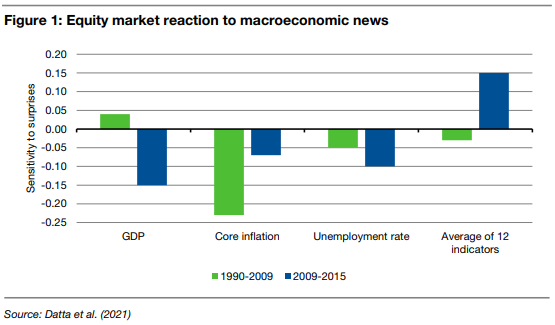

Ok, so I am not a fan of PPP or monetarist theories of inflation. So be it, not every theory works, but some do and some are quite useful. My classic counterargument is a study by Deepa Datta and his colleagues from 2021 that investigated the reaction of equity markets, the oil price, and Treasury yields to macroeconomic surprises. The twist about this study is that it compares the reaction of financial markets to macroeconomic news before and after the financial crisis of 2008. Below is the chart for equity markets, and in the paper you can find the data for oil and government bonds.

What worries me less is not that the size of the reaction of equity markets to macroeconomic news changes over time, but that the sign and the direction of the equity market reaction changes. On average, over 12 key macro indicators, the reaction of equity markets after the financial crisis goes in the opposite direction from before the financial crisis. Now explain this with your nice macro theory…

Even worse, if any theory can be upended within a couple of years to the degree that it literally points you in the wrong direction, why invest your hard-earned savings based on such a theory? And this is the fundamental problem behind my hesitation to use any theory in my work. As a strategist, I am paid to help investors make money. And as an investor, I am interested in the world as it is, not how it should be. I love discussing theories and models over a drink or at a (very nerdy) dinner party, but when it comes to my job, I am an empiricist. I will be driven by experimental and real-life evidence, not by textbook theories.

“But wait”, I can hear the economists complain (and I apologise to all economists for picking on you, I mean no harm and I stress – as in Part 1 – this is a personal view). The empirical evidence you showed above is taken from a very short period of time of a couple of years or a decade or two. That doesn’t disprove the theory. It only shows that one needs to collect more data. Let me address that argument tomorrow in part 3…

Thought of the Week features investment-related and economics-related musings that don’t necessarily have anything to do with current markets. They are designed to take a step back and think about the world a little bit differently. Feel free to share these thoughts with your colleagues whenever you find them interesting. If you have colleagues who would like to receive this publication please ask them to send an email to joachim.klement@liberum.com. This publication is free for everyone.